Heat Emergency Awareness and Treatment (HEAT): A cluster randomised trial to assess the impact of a comprehensive intervention to mitigate humanitarian crisis due to extreme heat in Karachi, Pakistan

This case study series documents the experience of R2HC-funded research teams in engaging with people affected by crisis. The full case series can be found here.

STUDY BACKGROUND

Heat Emergency Awareness and Treatment (HEAT): A cluster randomised trial to assess the impact of a comprehensive intervention to mitigate humanitarian crisis due to extreme heat in Karachi, Pakistan

A research team from the Johns Hopkins University of Medicine carried out this research.

Extreme temperature, primarily in the form of heatwaves, have been identified as the second highest cause of weather-related mortality after storms. Urban settings are at higher risk of adverse outcomes following exposure to extreme heat. Despite this risk, knowledge gaps persist in relation to approaches to better respond to extreme heat events.

This research proposed a community-based two-arm cluster-randomised controlled trial and a hospital-based intervention. Sixteen clusters in Korangi District in Karachi, Pakistan, were randomised to receive an education and treatment ‘bundle’, designed to reduce heat-related morbidity and mortality.

APPROACHES TO ENGAGEMENT WITH PEOPLE AFFECTED BY CRISES

DESIGN PHASE

Research quality

The importance of ensuring research quality honours the time and efforts of those participating in the research. The PI highlighted the importance of applying high regulatory standards, even in complex environments. In relation to conducting good quality research in settings affected by disasters, he said: “often the expectations for quality of science are low… [however], these communities deserve interventions based on the best evidence possible”.

Relevance of the problem

Karachi had seen a significant heatwave in 2015. The study team was aware of many people who had suffered and been unable to access care. This acknowledged problem was discussed with the research team by the PI: “When I pitched the idea of working on heat with colleagues everyone jumped on it – it’s an important problem.” At this stage the research question was not discussed with the community, but with local partners.

How participation was incorporated

Limited existing knowledge necessitated community-informed intervention planning

As there is a relatively limited existing evidence-base related to education and treatment packages for extreme heat, the research team felt it was critically important to work closely with local communities to better define the problem and a relevant intervention.

“We could only come up with good ideas in terms of intervention if we learned from the community. I knew there was a lot of wisdom and things we could learn from people who are often not asked. This became a selling point for the grant (I think). It gives me a lot of satisfaction in the confidence of [knowing] what we did is learn from the communities”

– Junaid Razzak, Principal Investigator

The study team were eager to develop a community health programme that addressed the needs of the community. The longstanding relationship that the PI and the local research team and partners had with the community allowed for engagement to develop the programme.

“We wanted to come up with a community health programme that addressed the need based on what the community wanted, and not based on the government or others.”

– Junaid Razzak, PI

Cascading design process

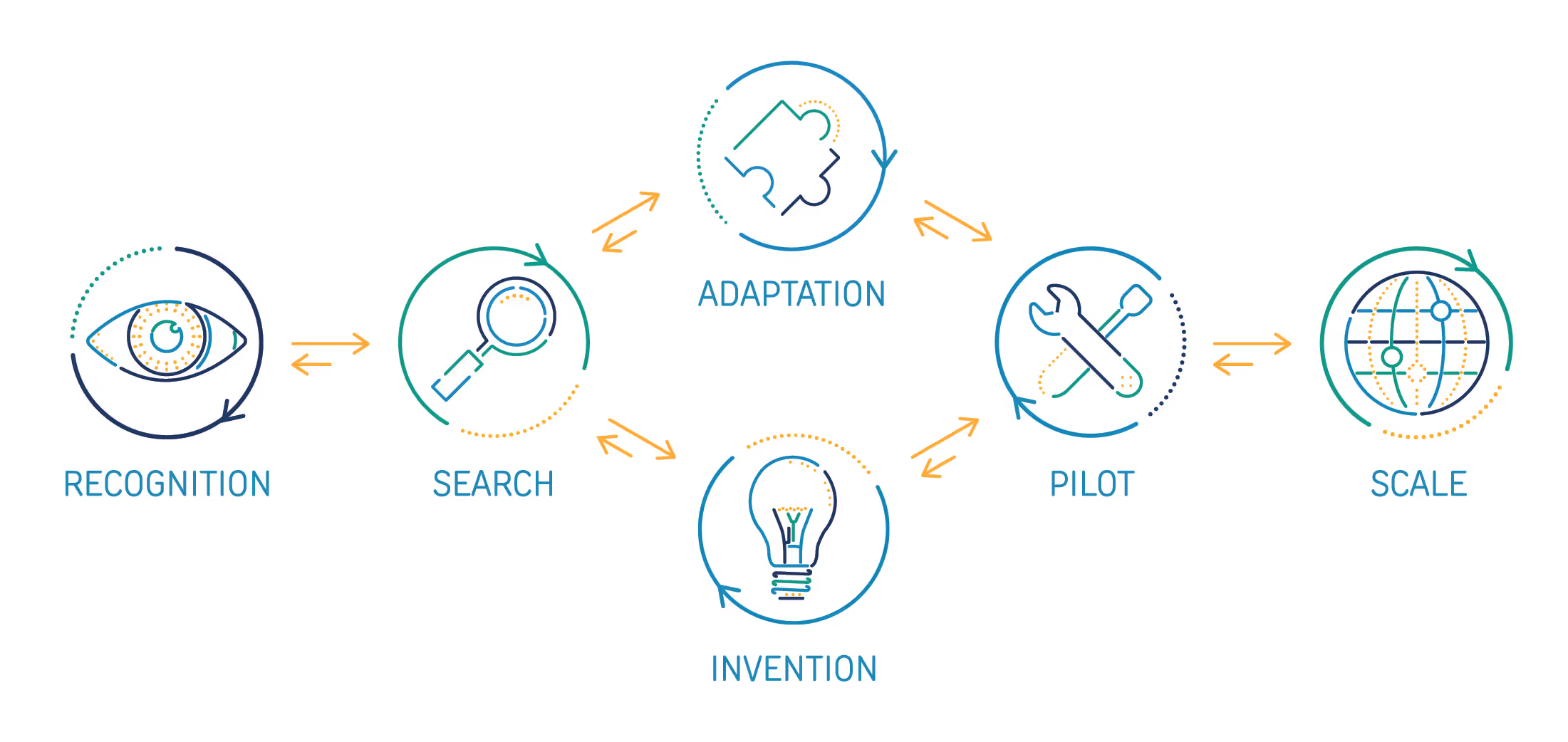

The design of a ‘community-based HEAT intervention’ was based on multiple staged conversations. First the team identified existing literature and best practices, then this was discussed extensively with community health workers (CHWs) in the local context to understand their perspectives on the proposed design. The team worked closely with the CHWs to take the concept to the community and then to return to the research team with feedback.

The research team felt it was important for locally trusted people to be talking to the community. It was felt that if individuals were to “go from the US, or even as a physician, and ask questions, then people might not be forthcoming; however, if their neighbour goes in and asks questions, they might be.”

Managing expectations

“When we started talking about the intervention, they asked if we could fix the water or electricity issues. The expectations were more than what we could deliver and managing the expectations was an issue”

– Junaid Razzak, PI

Some of the proposed interventions to reduce temperatures in heat waves recommended options such as fans, showers or changing the time of day for cooking. The team acknowledged that these were issues that they were not able to address as part of the study.

The research took an iterative approach, by developing a set of interventions, holding many conversations where feedback could be elicited, refining interventions and then returning for more feedback. It was the process of development that became the focus of the study, as opposed to the development of the final product intervention and testing of it.

IMPLEMENTATION PHASE

Participatory data collection

Data collection was conducted by women in the community – this decision was made as these women would not be seen as outsiders because they came from the same neighbourhoods as those being interviewed. Efforts were made to ensure that the conversations held during data collection were relaxed and free flowing.

“Few times we went into homes, there’d be a lot of chit-chats. Questions that could have been asked in ten minutes would take half an hour, because there were discussions about what was going on in the community”

– Junaid Razzak, PI

POST-RESEARCH PHASE

Inadequate time for dissemination

The short time frame of the study was a hindrance to meaningful participation at community level in the dissemination phase. It would have been ideal to have multiple meetings with the community to present the findings, but this only occurred once.

Scaling up of the approach

The discursive approach to talking about and identifying solutions to reduce the impacts of heat extremes has been taken up by the Aga Khan University and the Aman Foundation and they have conducted this work with health workers in preparation for the hot season.

ENABLING FACTORS

There were several enabling factors that facilitated community participation in this work including:

- The HEAT problem was widely accepted as a major extreme heat incident had happened just two years before the study.

- The PI had pre-existing relationships with partners in the local area: “People often knew the people behind the study… they knew me, they didn’t care about Johns Hopkins, or other names”

BARRIERS TO PARTICIPATION

The perception by the community of the study not being able to offer tangible incentives hindered participation.

FIND OUT MORE

To find out more, please see the https://www.elrha.org/project/heat-heat-emergency-awareness-treatment-bundle-trial/study profile.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Junaid Razzak for his expertise and reflections.