Uncovering resilience

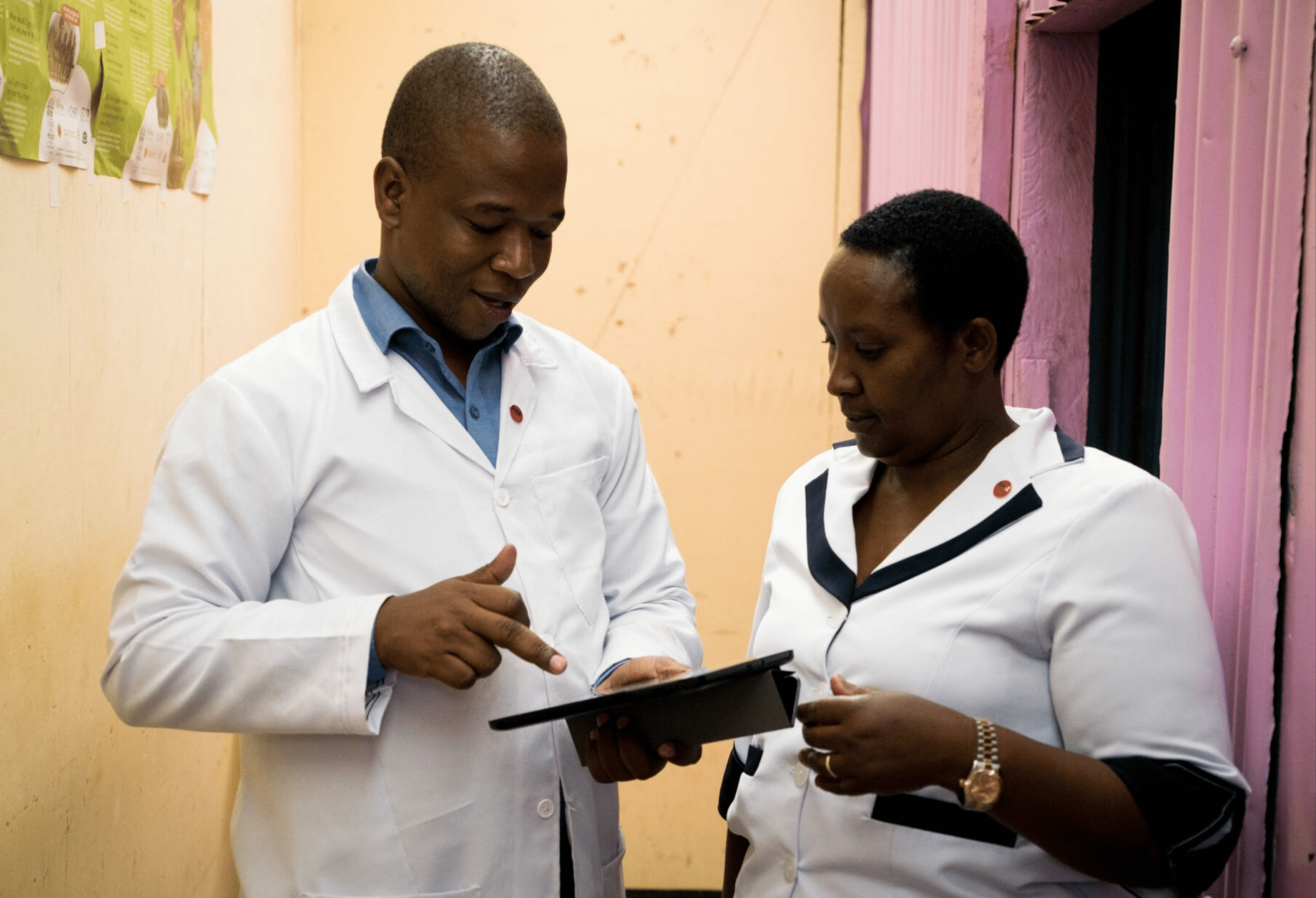

[caption id=attachment_8096"align="alignleft" width="300"]

©2017 UNRWA Photo by Maysoun Jamal Mustafa

Palestine refugee from Syria beingexamined at Beddawi Health Centre, Lebanon[/caption]

As part of an R2HC funded project exploring health systemresilience in the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA)* , I had theopportunity to undertake key informant interviews in UNRWA clinics in Lebanon and Jordan.

Spanning a period ofapproximately a month, I visited health care centers offering primary care services to displaced Palestine refugees inthe region. Notably, both countries had a substantial population of Palestinian refugees – displaced either due to theprevious Arab-Israeli wars or more recently due to the Syria crisis.

Despite similar origins, Palestinianrefugees in Lebanon and Jordan face substantially different realities. Palestinians in Lebanon are particularly poor andcan be said to belong to a socio-economically deprived social stratum: they have poor access to national health services(outside UNRWA) and the restrictions on their right to employment mean they cannot enter the local job market.Palestinians can only be employed in certain professions and mostly reside inside overcrowded camps with poor housingconditions; it is not uncommon to see guarded entry and exit check points at Lebanese refugee camps and this was quitestriking for me as a Lebanese citizen while passing through.

[caption id="attachment_8094" align="alignleft"width="300"]

© UNRWA 2016 Photo by Mohammad Magayda

Various Palestine refugees waiting fortheir appointments at Zarqa Health Centre, Zarqa, Jordan[/caption]

In contrast, Palestinians in Jordan seemed toenjoy better living conditions – mainly due to enjoying improved social and political rights: most have full citizenshipand access to national health services as well as jobs. While Palestinian refugees displaced by the Arab Israeli warshave adapted to the circumstances in both countries, the recent influx of Palestine refugees from Syria has placedadditional burdens on both Jordan and Lebanon as well as UNRWA health services. In total, about 300,000 refugees arecurrently accommodated in Lebanon, and 2,000,000 in Jordan and UNRWA is the main agency responsible for providingessential primary care services to this population.

Our project explores how resilient and adaptive the UNRWAhealth system has been in coping with this great influx of Palestine refugees from Syria. My data collectioninvestigated this issue via interviews with health care personnel at UNRWA primary care clinics. I wanted to understandhow health service delivery changed during the Syria crisis – how processes are still changing today.

Datacollection was both fraught with challenges as well as highly rewarding. As expected with interviews focused on servicedelivery, quite a few of the approached participants felt apprehensive about taking part in the study and avoided havingtheir voices recorded. They were highly suspicious of the safety of disclosing information (despite assurances of theconfidentiality and anonymity of their answers), though this changed quickly once we started speaking: for some, theinterview became a means to vent about work-related pressures and grievances.

[caption id="attachment_8095"align="alignleft" width="300"]

© UNRWA 2016 Photo by Mohammad Magayda

A nurse measures Palestine refugee childweight at Irbid health Centre, Irbid, Jordan[/caption]

Most informants I spoke to were interesting and highlydedicated individuals. Health care personnel in UNRWA is mostly Palestinian and this means that staff feel a sense ofduty and camaraderie with the populations they serve as well as those newly displaced by the Syria conflict. A majorityof participants in Lebanon reported choosing to come to work in difficult political and social conditions, despite highworkloads and limited remuneration. Health care staff showed incredible commitment towards their profession and wereparticularly emotional about the plight of refugees: as Palestinian refugees themselves, it was incredibly traumatic tothem to see the impacts of a newly unfolding civil war.

One key ‘resilience’ characteristic from our interviewswas the dedication of health care staff. We are currently in the process of analyzing our interviews from Lebanon andJordan and we hope to soon collect additional valuable insights on service delivery from health care professionalsactive in UNRWA clinics in Syria. To do this, we have recruited a staff member already active in Syria under UNRWA’sRelief and Social Services who will conduct interviews in safe selected sites. Having an insider’s perspective for datacollection will prove particularly insightful as our data collector already has substantial experience with both theconflict and the connected challenges of care delivery. This may also result in difficulties, though we will be carefulnot to introduce bias in our research.

Continuing ahead, I am looking forward to seeing the results of ourupcoming group model building sessions in February and May, which will involve UNRWA staff, community associations’representatives as well as national Ministry of Public Health representatives from Lebanon and Jordan. The feedback fromthese participants, each having a different field of expertise, will enrich our understanding of the UNRWA health systemand the issues it faces – eventually this will help us identify optimal strategies for ensuring health service deliveryin adverse conditions.

Author: Zeina Jamal, Research Coordinator at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

*There is a distinction between Palestine and Palestinian refugees. Not all Palestinian refugees are Palestine refugees according to UNRWA. Only those fleeing between the years 1948- 1949 are called Palestine refugees and are entitled to UNRWA services.[captionid="attachment_8096" align="alignleft" width="300"]

©2017 UNRWA Photo by Maysoun Jamal Mustafa

Palestine refugee from Syria beingexamined at Beddawi Health Centre, Lebanon[/caption]

As part of an R2HC funded project exploring health systemresilience in the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA)* , I had theopportunity to undertake key informant interviews in UNRWA clinics in Lebanon and Jordan.

Spanning a period ofapproximately a month, I visited health care centers offering primary care services to displaced Palestine refugees inthe region. Notably, both countries had a substantial population of Palestinian refugees – displaced either due to theprevious Arab-Israeli wars or more recently due to the Syria crisis.

Despite similar origins, Palestinianrefugees in Lebanon and Jordan face substantially different realities. Palestinians in Lebanon are particularly poor andcan be said to belong to a socio-economically deprived social stratum: they have poor access to national health services(outside UNRWA) and the restrictions on their right to employment mean they cannot enter the local job market.Palestinians can only be employed in certain professions and mostly reside inside overcrowded camps with poor housingconditions; it is not uncommon to see guarded entry and exit check points at Lebanese refugee camps and this was quitestriking for me as a Lebanese citizen while passing through.

[caption id="attachment_8094" align="alignleft"width="300"]

© UNRWA 2016 Photo by Mohammad Magayda

Various Palestine refugees waiting fortheir appointments at Zarqa Health Centre, Zarqa, Jordan[/caption]

In contrast, Palestinians in Jordan seemed toenjoy better living conditions – mainly due to enjoying improved social and political rights: most have full citizenshipand access to national health services as well as jobs. While Palestinian refugees displaced by the Arab Israeli warshave adapted to the circumstances in both countries, the recent influx of Palestine refugees from Syria has placedadditional burdens on both Jordan and Lebanon as well as UNRWA health services. In total, about 300,000 refugees arecurrently accommodated in Lebanon, and 2,000,000 in Jordan and UNRWA is the main agency responsible for providingessential primary care services to this population.

Our project explores how resilient and adaptive the UNRWAhealth system has been in coping with this great influx of Palestine refugees from Syria. My data collectioninvestigated this issue via interviews with health care personnel at UNRWA primary care clinics. I wanted to understandhow health service delivery changed during the Syria crisis – how processes are still changing today.

Datacollection was both fraught with challenges as well as highly rewarding. As expected with interviews focused on servicedelivery, quite a few of the approached participants felt apprehensive about taking part in the study and avoided havingtheir voices recorded. They were highly suspicious of the safety of disclosing information (despite assurances of theconfidentiality and anonymity of their answers), though this changed quickly once we started speaking: for some, theinterview became a means to vent about work-related pressures and grievances.

[caption id="attachment_8095"align="alignleft" width="300"]

© UNRWA 2016 Photo by Mohammad Magayda

A nurse measures Palestine refugee childweight at Irbid health Centre, Irbid, Jordan[/caption]

Most informants I spoke to were interesting and highlydedicated individuals. Health care personnel in UNRWA is mostly Palestinian and this means that staff feel a sense ofduty and camaraderie with the populations they serve as well as those newly displaced by the Syria conflict. A majorityof participants in Lebanon reported choosing to come to work in difficult political and social conditions, despite highworkloads and limited remuneration. Health care staff showed incredible commitment towards their profession and wereparticularly emotional about the plight of refugees: as Palestinian refugees themselves, it was incredibly traumatic tothem to see the impacts of a newly unfolding civil war.

One key ‘resilience’ characteristic from our interviewswas the dedication of health care staff. We are currently in the process of analyzing our interviews from Lebanon andJordan and we hope to soon collect additional valuable insights on service delivery from health care professionalsactive in UNRWA clinics in Syria. To do this, we have recruited a staff member already active in Syria under UNRWA’sRelief and Social Services who will conduct interviews in safe selected sites. Having an insider’s perspective for datacollection will prove particularly insightful as our data collector already has substantial experience with both theconflict and the connected challenges of care delivery. This may also result in difficulties, though we will be carefulnot to introduce bias in our research.

Continuing ahead, I am looking forward to seeing the results of ourupcoming group model building sessions in February and May, which will involve UNRWA staff, community associations’representatives as well as national Ministry of Public Health representatives from Lebanon and Jordan. The feedback fromthese participants, each having a different field of expertise, will enrich our understanding of the UNRWA health systemand the issues it faces – eventually this will help us identify optimal strategies for ensuring health service deliveryin adverse conditions.

Author: Zeina Jamal, Research Coordinator at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

*There is a distinction between Palestine and Palestinian refugees. Not all Palestinian refugees are Palestine refugees according to UNRWA. Only those fleeing between the years 1948- 1949 are called Palestine refugees and are entitled to UNRWA services.

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Related articles

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.