‘How we continued when we had to work 24/7? Commitment‚ nothing but commitment!’

Immigration is a topic that is rarely out of the headlines these days. There is large discussion around how western European countries are coping with the influx of migrants from Syria. But how do the countries closest to the conflict cope, since they receive the largest numbers of displaced peoples?

Our project explores the concept of ‘health system resilience’, more specifically trying to identify what exactly is ‘resilient’ about health service delivery within the UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) care system in the Middle East.

My colleague Zeina Jamal introduced this exciting line of work, alongside first impressions gathered across interviews in Lebanon and Jordan, in a previous blog. Within this project my colleagues at Queen Margaret University in Scotland and the American University in Beirut in Lebanon and I are exploring the changes in health service delivery patterns in Lebanon, Jordan and Syria from 2010 through to today. We focus on UNRWA health services to Palestine refugees and aim to identify what characteristics of the UNRWA health system make it resilient to shock. That is: given the impacts of the Syria conflict – either active disruption of health services or mass displacement of populations from Syria into neighboring Lebanon and Jordan – how has UNRWA been able to cope with its service delivery and what lessons can we learn from this system for application in other similar settings?

The concept of health system resilience is elusive and arguably, an elusive concept is one that is incredibly difficult to study. Late February this year, my colleagues and I attempted to elicit a first account of ‘health system resilience’ via a group-model building workshop in Beirut. Here, we asked a room full of UNRWA health service managers, active at country, region or facility level, as well as health care staff (doctors, nurses and clerks) and community representatives from across Lebanon what had changed in relation to service delivery given the mass influx of displaced Palestine refugees from Syria into Lebanon.Immigration is a topic that is rarely out of the headlines these days. There is large discussion around how western European countries are coping with the influx of migrants from Syria. But how do the countries closest to the conflict cope, since they receive the largest numbers of displaced peoples?

Our project explores the concept of ‘health system resilience’, more specifically trying to identify what exactly is ‘resilient’ about health service delivery within the UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) care system in the Middle East.

My colleague Zeina Jamal introduced this exciting line of work, alongside first impressions gathered across interviews in Lebanon and Jordan, in a previous blog. Within this project my colleagues at Queen Margaret University in Scotland and the American University in Beirut in Lebanon and I are exploring the changes in health service delivery patterns in Lebanon, Jordan and Syria from 2010 through to today. We focus on UNRWA health services to Palestine refugees and aim to identify what characteristics of the UNRWA health system make it resilient to shock. That is: given the impacts of the Syria conflict – either active disruption of health services or mass displacement of populations from Syria into neighboring Lebanon and Jordan – how has UNRWA been able to cope with its service delivery and what lessons can we learn from this system for application in other similar settings?

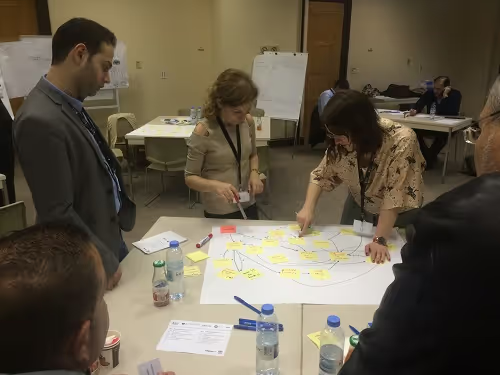

The concept of health system resilience is elusive and arguably, an elusive concept is one that is incredibly difficult to study. Late February this year, my colleagues and I attempted to elicit a first account of ‘health system resilience’ via a group-model building workshop in Beirut. Here, we asked a room full of UNRWA health service managers, active at country, region or facility level, as well as health care staff (doctors, nurses and clerks) and community representatives from across Lebanon what had changed in relation to service delivery given the mass influx of displaced Palestine refugees from Syria into Lebanon.

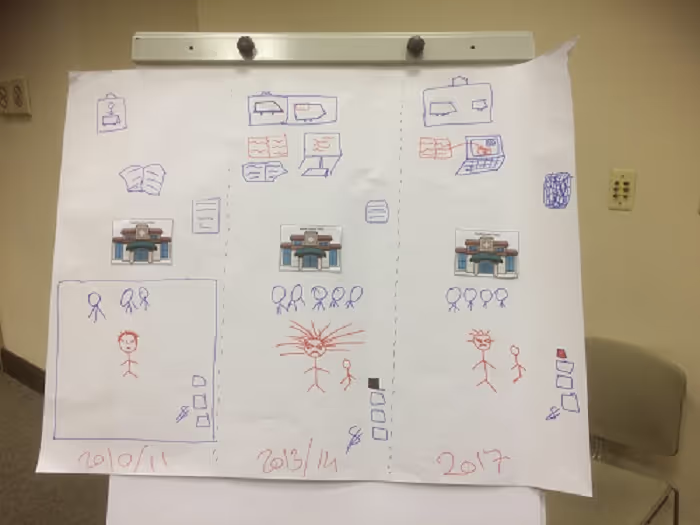

Our workshop participants rushed to tell us their stories and we captured these in simple pictorial form. Our participants sketched long queues of people at clinic doors in the early days of displacement, more wads of money to indicate an increase in financial resources as the conflict progressed, new human resources hires, and increased medicines and equipment stock. Notably, problems that the system suffered from were depicted as difficulties with registering new patient arrivals given the lack of a functioning computerized record system; different patient care expectations - national health care in Syria had been easily accessible and Palestine refugees were therefore not used to seeking care within UNRWA clinics. The new influx of people – many with their own psychological problems and tensions – also resulted in conflicts between the refugees settled within Lebanon and those newly arriving; in time, conflicts were resolved and a community structure emerged.

In the meantime, the UNRWA care system itself had to cope. Participants explained that in Lebanon, receiving new refugees within the UNRWA system was not a substantial problem at first as the system itself had been designed for emergency situations: "Unlike other NGOs, UNRWA’s infrastructure is well equipped to cope with high number of patients. Our clinics are big and our health teams are trained to deal with big number of patients…" - Area Health Manager. Treating large numbers of patients, moving medicine stock from one area to another, hiring new temporary staff, changing record-keeping protocols to capture all relevant patients – UNRWA protocols were already in place to guide all of this. The challenge, rather, was the move beyond emergency protocols. Given the situation in Syria – a war showing no respite or sign of cessation – UNRWA had to move from emergency to ‘routine’ operation.

It is these circumstances that our participants recounted as the challenge: a protracted conflict situation in a neighboring country; delivery of services to a new, poor and psychologically burdened population and the move from emergency operation to normal work. The latter of course, was not simple: since 2010 UNRWA had been undergoing a series of health system reforms: decentralization of decision-making to allow for better local and regional control over resources and a shift in priorities from preventive to curative services. What happens to short-term hires in such a system, how are the psychological needs of the displaced population now met, how is care quality and continuity maintained and what affect do community dynamics and local clinic leadership have on the success of care delivery?

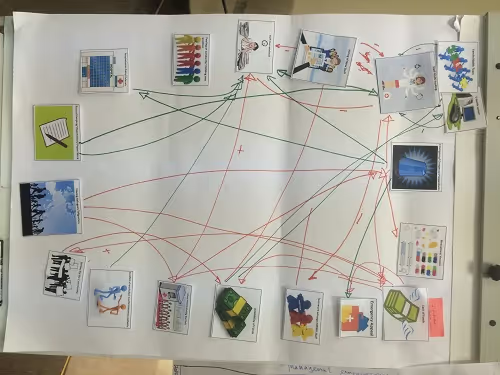

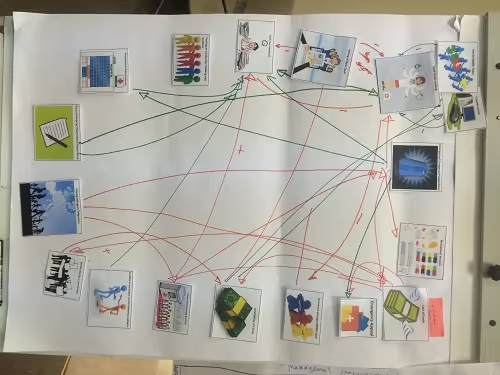

These are the complex questions our research seeks to address. And with the help of this workshop we have already made strides in the right direction. Via a series of engaging activities, our participants sketched their own accounts of the UNRWA system and its resilience. Links between the influx of patients, the necessary medicines and human resources, local decision making structures were all sketched out. Questions relevant to UNRWA’s functioning during this time were also slowly being answered. For example, we asked: “Were there sufficient staff to deal with the sharp increase in patient numbers?” ‘Not at first, but we eventually hired new staff– they helped us manage, but only if appropriately trained.’ Links between staff training, human resource capacity, UNRWA hiring protocols thus started taking shape in our diagrams.

The most important question we had to ask, however – specifically after realizing most of our participants noted the long working hours and increase in working days due to the influx of refugees – was: “How did you cope, how did you manage to keep working?” The answer to that question will certainly constitute the heart of our research and of our understanding of UNRWA’s system and what enables it to function:

‘How we continued when we had to work 24/7? Commitment, nothing but commitment! We understand their plight, are refugees ourselves – they are just like us’

Author: Karin Diaconu, Research Fellow

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Related articles

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.