Who’s Taking Ownership of Surface Water Anyway?

;

In the last blog, topics related to the design trajectory of camps were discussed, but how about the institutional barriers?

The UN is not immune to the disorder, created out of the intended bureaucratic order which often plagues large organisations. Part of the due process in the times of an emergency will see a camp go through site selection, planning, design and construction. Finally, the management phase is carried out by the government authority in which the camp resides and the humanitarian partners from the Camp Coordination and Camp Management cluster (CCCM).

However, the pace at which a camp is built can vary from a few months to a year, bearing in mind, they often house many thousands of people, creating small cities over time. A population of a city in a year, in a new place, once never inhabited, can, in fact, be limited by the very institutional and bureaucratic arrangements it is born into. Why? Because is in the embedded practices of the humanitarian sector.

History has shown itself to create, for one as a topic of conversation – drainage, a system by which water is conveyed as quickly as possible out of an urban space.

The earliest evidence in the management of surface and wastewater existed in its most rudimentary form in early Babylonian and Mesopotamian Empires in Iraq between 4000–2500 BC. The model adopted in cities today and in camps is reminiscent of those used by Babylonian drainage pioneers. It’s these adopted systems in the camps, coupled with structural embeddedness (inter-agency communication and networks) that create the bureaucratic barriers.

During an interview with Mr Rafid Aziz, a WASH Specialist at UNICEF, the question was asked as to who takes on the responsibility and ownership of WASH at the initial phases of a camp’s life. He explained that during the Syrian crisis and refugee movement into Kurdistan, starting in early 2012, there had been a debate between UNHCR and UNICEF on who handled drainage within the camps.

Drainage was not considered properly from the start.

Take for example Domiz refugee camp, in northern Dohuk, which was created on an unlevelled terrain. Blackwater and greywater were both conveyed through settling tanks. High costs existed around de-sludging (removal of waste from cesspits). In some cases, the size of the settling tanks was not designed properly to provide the necessary holding capacity. These settling tanks were not watertight either. During peak flow of user wastewater, and additional surface water runoff, the settling tanks would overflow. The wastewater may have been diluted, however, there were definitely contaminants due to the foul smell present. This experience was from 5-6 years ago, however, Domiz refugee camp is a good example of how drainage was neglected at the emergency stage of planning, design and construction, due to confusion on defined roles and responsibilities.

This point has been highlighted in a paper by Brian Reed, entitled, “Surface water in temporary humanitarian environments,” where the author elicits to a lack of institutional ownership and responsibility. Drainage facilities here were introduced by the French Red Cross. Bear in mind that the approach was still simply a case of conveyance out of the camp, aimed at improving the state of affairs described earlier, by quickly removing the issue of heightened peak flows.

Camps are therefore left with a hastened desire to improve, a visit to Qustapha camp illustrated this. These improvements have meant water of any sort is conveyed and disregarded once it leaves the fence of the camp, becoming somebody else’s problem.

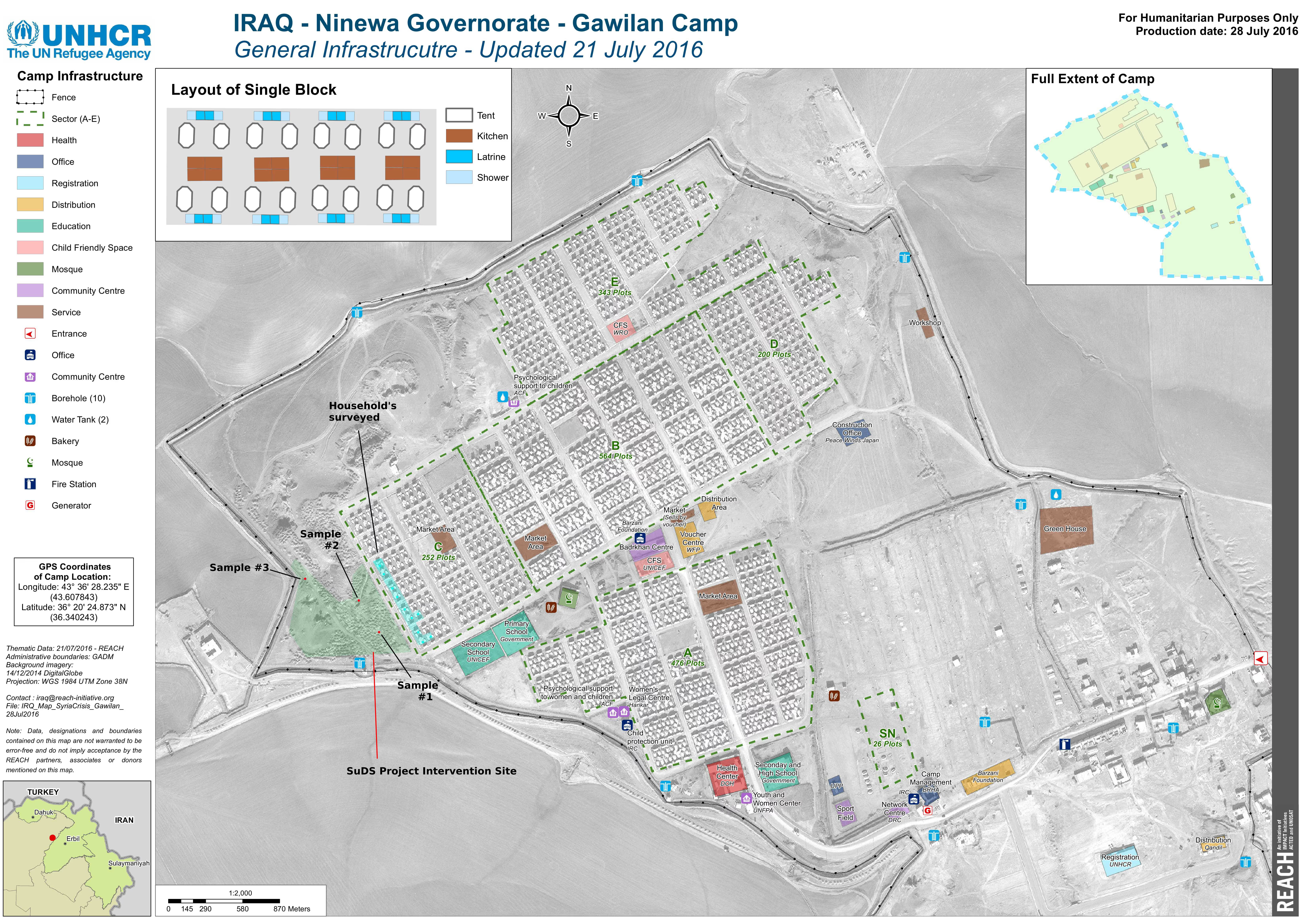

A visit with a team from a local environmental company, Mapcom, allowed further empirical research into what the quality, specifically, and quantity of water looked like in Gawilan camp, where a proposed site for the introduction of sustainable drainage systems (SuDs) components is underway. To see a larger version of the image below, please click here.

In the next blog, I discuss the process of water sampling and the results.

This video (click to watch) highlights the presence of standing surface water, and due to the odour, it suggested both leachates from the waste and greywater mixed into the drained water. Soil types will be further discussed in a later blog, which elicits to the presence of underlying silt/clay horizons.

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Related articles

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.