Welcome to South Sudan: How the Research Began

How the research began

In 2013, the Maban County refugee camps in South Sudan faced major outbreaks of Hepatitis E. Mortality levels were high, and distressingly, it was pregnant women who were most vulnerable.

Hepatitis E has no specific treatment, so we in MSF, along with other agencies on the ground, threw everything we had at interrupting the transmission of this water-related pathogen. We worked to expand sanitation coverage, enhance hygiene and hand-washing activities, and improve water quantity and quality in the camps.

As we worked to improve water quality, we were focused on achieving the Sphere Project guidelines, which stipulate what free residual chlorine (FRC) levels should be at camp water distribution points. The chlorine is there of course, first, to disinfect the water and then to protect it against potential recontamination.

Even as we achieved the Sphere FRC guidelines at tapstands, when we went to refugees’ shelters to check the water quality there, we often found no detectable chlorine—the water was totally unprotected where people were drinking it!

Because Hepatitis E is a disease we don’t know a lot about, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) came in to investigate the outbreak. They, along with Oxfam, carried out systematic surveys of household water quality. They found that about 40% of households that collected water from chlorinated sources had no detectable chlorine in their stored water. Another group from the University of Barcelona came in to investigate viral contamination in the environment. They found human adenoviruses—an indicator of human fecal contamination—in the stored water in peoples’ shelters.

This was really concerning for us: we were achieving the Sphere Project guidelines at the tapstands but we found the water to be unprotected and even fecally contaminated where people were consuming it—in the midst of a major disease outbreak which could well be transmitted via drinking water!

The results forced us to ask: what was happening to the chlorine protection in the water between distribution and consumption? It also raised a more general question: where did these guidelines come from anyway?

So, where did these guidelines come from?

Now, we didn’t have time to look into this question in the field, we were too busy reacting to the Hep E outbreak. But when I came back from South Sudan and did some digging, I found that the Sphere Project guidelines for water quality trace back to the WHO Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality.

The problem is however that the WHO guidelines are based on experience with municipal piped water systems—in cities! In a city, we drink water right from the tap in a relatively hygienic setting. In a refugee camp on the other hand, people collect water at public tapstands, carry the water through the camp back to their shelters, and then store and use that water for up to a day or more—all in a setting where environmental hygiene may be less than perfect.

It was no wonder then that the Sphere Guidelines were failing to ensure safe water at the point of consumption in South Sudan. Wewere stunned to learn that these guidelines—used by humanitarian agencies the world over—were based on no evidence whatsoever from the field.

Faced by this knowledge gap firsthand in South Sudan, we launched research to begin building evidence on water quality in emergency settings, refugee and IDP camps. Specifically, we were interested in studying chlorine decay between distribution and consumption in the camp setting in order to determine what chlorine levels should be at tapstands in order to ensure that water is adequately protected when people consume it at home.

Our research in South Sudan

We carried out this research in South Sudan, and generated some preliminary recommendations on how to improve water safety. We recommended that FRC at tapstands be increased to 1.0 mg/L—irrespective of outbreak, pH and turbidity conditions. This would ensure residual chlorine protection of at least 0.2 mg/L up to ten hours post-distribution, according to our modeling. Because the temperatures were so high and the ambient hygienic conditions so poor in South Sudan, it did not seem possible to maintain chlorine residual and protect the water for longer than ten hours. (See more)

We made these recommendations for South Sudan but did not know if our findings would be externally valid—could they be generalized to other camps around the world? We knew we had to expand globally, to camps in diverse environmental and climatic settings. It would be impractical to go to every camp, so instead we sought to select camps that were representative of the regions in which we face major displacement crises today.

Therefore, in 2014, in collaboration with UC Berkeley, MSF, and UNHCR, we expanded the study to the Azraq refugee camp in Jordan. Azraq is a planned camp with excellent WASH services and a very high standard of ambient sanitation in a hot desert setting. We visited Azraq first in summer 2014 to carry out our study.

Expanding the study

In 2015, we received the support of HIF to expand the study further. We returned to Azraq again, this time in the winter, in order to hold our site constant and more closely investigate the effect of seasonality and temperature on chlorine decay.

So that’s a bit of background on how this research project emerged. In my next post, I’ll tell you more about our findings from Jordan and what they tell us about how our emergency water treatment guidelines should be designed in order to accommodate seasonality effects.

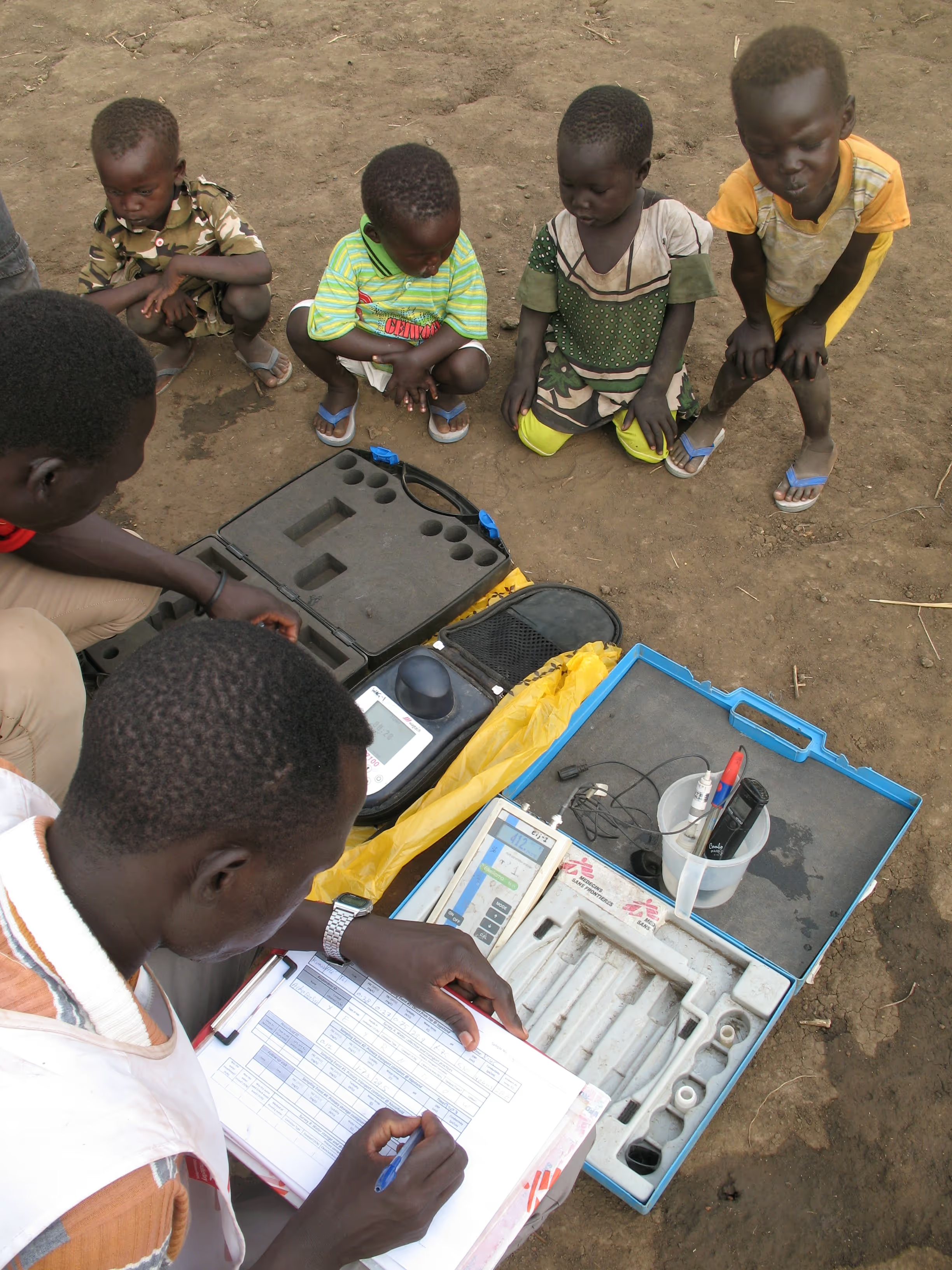

Feature Photo: Science class in Gendrassa Camp, South Sudan (2013). Credit: MSF.

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Related articles

.png)

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.