Making Online Training A Social Experience

Can big data make learning a social experience?

We explore the evidence, looking at the intrapreneurship training developed by TechChange and Ashoka. We compare it to the ebuddi approach and look at the opportunity for promoting a more personal and social learning experience. But why is this so relevant to the humanitarian sector?

The key challenge in a more decentralised and flexible humanitarian response is ensuring the local people have the relevant competencies, confidence and resources to respond. Local capacity building is more than imparting knowledge and testing whether it has been retained. Humanitarian responses are also social processes. Resilience is just as much about how people learn to work together, and support one another.

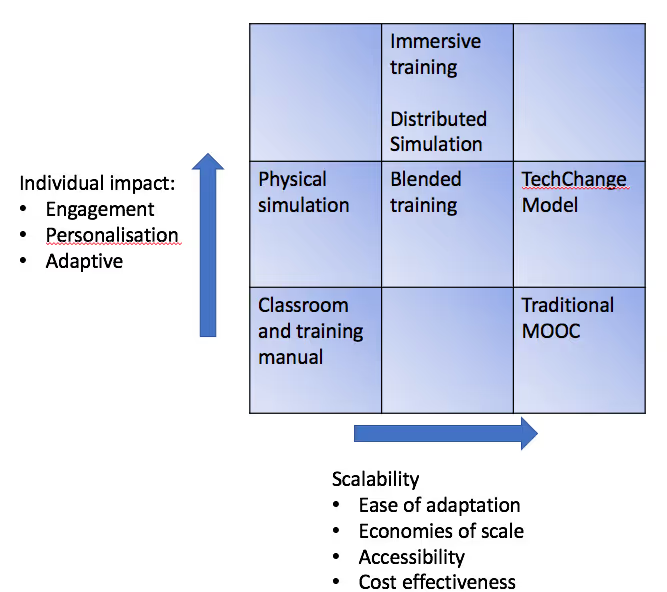

In this HIF project, we showed how simulation-based training with real life scenario complements could transform the traditional approach to training. But it is even better if the learning environment can bring people together from complementary functions, sectors, and viewpoints. The default approach to capacity building in the development and humanitarian field largely remains didactic, often ‘PowerPoint’ based, with some efforts to scale humanitarian capacity building using Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs).

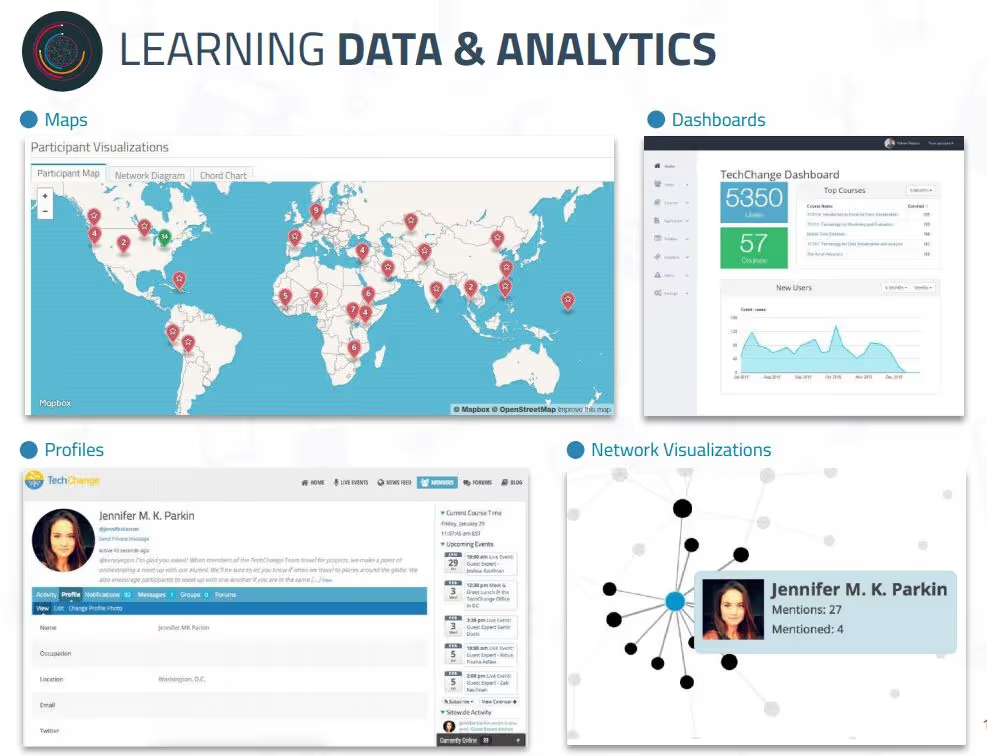

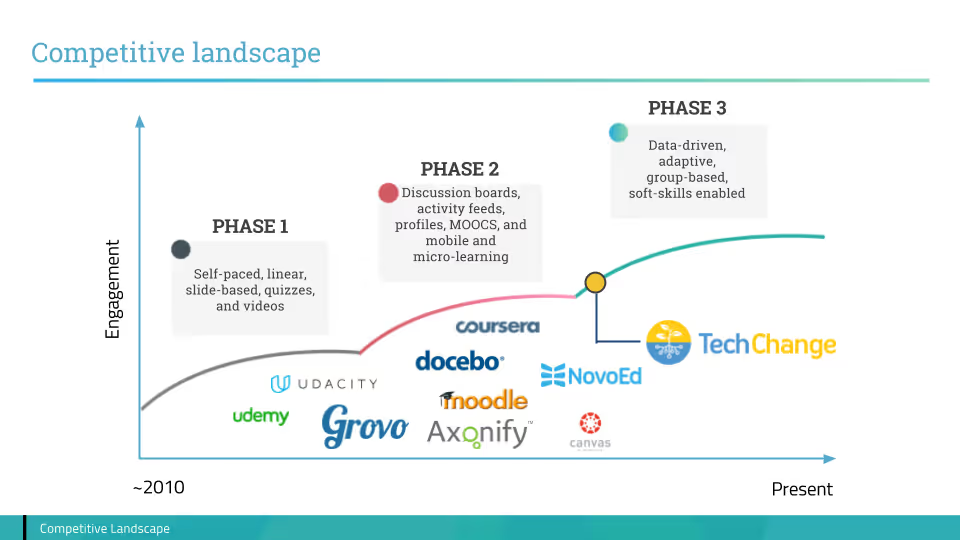

The impact of MOOCs has been disappointing. Many start them, few finish, and their impact is hard to measure. The courses often reflect the traditional ‘sage on the stage’ experience, as opposed to exploring the learning experience from the user. Chris Neu has explored the reasons for this in his blog ‘How Broadcast-Based Techno-determinism Fails EdTech’. His company TechChange, has been working with a range of partners in the development sector to offer a more personal ‘adaptive’ approach with a social element built into it.

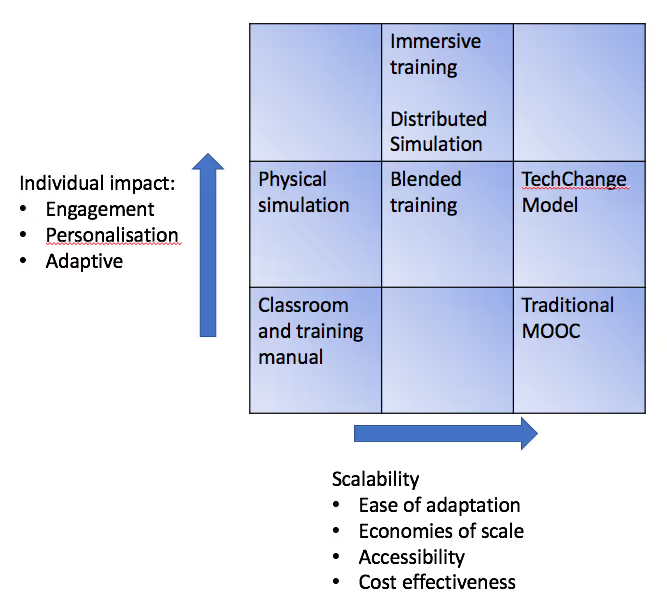

What does this mean in practice, and what is the evidence that it is actually better than the MOOC approach? The TechChange platform is being used by the Ashoka organization for their social intrapreneurship course. We evaluated this course discovering it to be much more interactive and adaptive than the traditional classroom-based approaches to teaching and the MOOCs we also evaluated. The TechChange platform offers a dynamic insight into the progress of a learner, how they are interacting with their peers, and tests knowledge and confidence with built-in evaluations. ‘Hardwiring’ quality assurance into training programmes can cut costs – dramatically simplifying the ‘Monitoring and Evaluation’ (something we designed into the ebuddi approach).

Ashoka’s TechChange based course typically takes 6-8 weeks of skill-building, with a mix of social activists, area experts, and people from the private sector. This is less intensive than the ebuddi approach (which is a blended approach) in both duration and structure, but it has its benefits from allowing a self-directed pace approach to learning. It does assume internet access (ebuddi does not), but its bandwidth requirements are modest. The TechChange approach employs a mix of personal messaging, chat boxes, discussion forums and real-world, team, project-based work, with official certification upon completion which is based not only on knowledge learning, but also on engagement during the course. This enables Peer-to-Peer interaction to be actively encouraged, tracked and rewarded turning the learning process into a social experience.

What is the impact of this approach? TechChange has 60-65% completion rates (10x industry average) based on 500 online courses and 50,000 students from 170 countries. 95% of alumni say they’d recommend the TechChange learning experience to a colleague. Whilst the TechChange approach may not have the impact and engagement that one might expect from a simulation-based experience, it benefits from being a platform that can be quickly adapted to different curricula.

But innovation in this field has many challenges. Few charities have the expertise in pedagogy to critically assess the limitations of conventional approaches, especially where donors may prefer to support an approach and cost structure they are familiar with. A cost recovery financing model of donors discourages innovation and approaches that require an upfront investment in development or adaptation which may require skills not available in-house.

The humanitarian sector urgently needs to embrace new approaches to empowering frontline workers – to give them the competences, knowledge and confidence to safeguard communities and people in the face of demands on humanitarian agencies far outstripping funds. At the start of the 2017 OCHA’s Emergency Relief Coordinator (ERC), then Stephen O’Brien, warned: “The scale of humanitarian crises today is greater than at any time since the United Nations was founded”.

Both TechChange’s platform and the ebuddi concept illustrate the opportunity we have to re-imagine local capacity building; the importance of a plurality of approaches and the fact we have practical, innovative and field-tested approaches we can build on.

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Related articles

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.